Summary: A field-building approach can help a foundation, a donor-advised fund, or giving program achieve greater strategic clarity and increased impact.

Be creative in designing grant strategy

All foundations and giving programs will struggle to find strategic focus at some point(s) along their life cycles. A grantmaking program that was once strong no longer seems to be having its intended effect. New trustees may be drawn to innovate. An influx of capital raises the stakes. Or – the program may be in its infancy, establishing its strategic focus for the first time.

The time-tested prescription for this unsettled condition boils down to three steps towards clarity: (1) take time to map the field, (2) listen and engage stakeholders, and (3) cluster key themes to analyze and decide on priorities.

In the best evidence of excitement and optimism, the planning process makes liberal use of colored sticky dots, Post-Its, and pads of newsprint.

We are not kidding when we say that strategy development is therapeutic. In our work with foundations and giving programs defining their giving strategies, we have seen how the process of learning and building something new brings fresh enthusiasm and an energized mission. People thrive when you give them permission to be bold and creative.

Deploy donor-advised funds for more than checkbook philanthropy

We were delighted when the Rudolph* family asked GMA Foundations to help them design a grantmaking strategy for their donor-advised fund. In doing so, these family members challenged the notion of donor-advised funds as “checkbook philanthropy” – a convenient way of channeling funds to a donor’s favorite charities. The Rudolph Family Fund would be increasing the amount of its charitable gifts for a short period and its donor advisors knew it could have a bigger impact if it carefully focused its resources.

The donor advisors wanted to help youth precariously near or tangled with the juvenile justice or social welfare systems. With dozens of high-quality organizations serving youth in the Boston area, finding a true leverage point would be essential.

Scan the field for emerging or missing connections

GMA’s first step was to map the field – formally known as a field scan. We tapped into our professional networks to compile and compare lists of organizations and nonprofit leaders, creating a specialized profile of approaches to our most vulnerable youth. This gave us an important vantage point in a forest of options. At first, the prospect of gaining focus seemed to shrink as our list of organizations grew longer. But like a puzzle, the patterns, connections, and clusters of activity in the field of youth development began to appear.

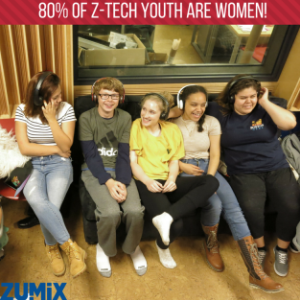

One beacon of activity that we recognized was the growth and success of programs using art, creativity, or expressive disciplines to promote youth development. These programs use self-directed, project-based, and experiential learning to engage youth. Most importantly, they had an ethos of “youth voice” as the driving force of the programs.

Find a conceptual framework

The field of creative youth development stood out to the trustees as fertile ground for many of the reasons described by Denise Montgomery, in the Rise of Creative Youth Development – published in the Arts Education Policy Review (6/16/16).

The Boston area already had a constellation of locally and nationally recognized leaders in the field. Their success encouraged the traditionally-minded state institutions serving youth to experiment with arts and music as strategy for their programs.

While much of the leadership in the field was home-grown, it turns out that the Massachusetts Cultural Council (MCC) happened to be a national champion of the creative youth development approach. MCC helped lead the way with seed funding and advocacy. Its report on creative youth development was both a conceptual framework and a call to action saying that the field of creative youth development had arrived.

Develop a portfolio of leading organizations

As in the field of investing, a good grantmaking portfolio helps create systematic coherence and balance. Grouping complementary grant possibilities in portfolios allows for comparison and the setting of clear boundaries that focus limited resources. We dramatically clarified the opportunities for impact when we narrowed the domain to a sub-set of organizations.

The donor advisors agreed to set up a grants program that would pledge significant multi-year operating support to a portfolio of six creative youth development organizations. The grants would help organizations tackle their “blue sky” goals, strengthening their work to serve young people better.

The Rudolph Fund found its focus beautifully defined in the field building work done by the Massachusetts Cultural Council and its national peer organizations such as the Creative Youth Development National Partnership. This donor-advised fund had renewed commitment to its mission.

Seek impact beyond individual outcomes

We are confident that the Rudolph Fund’s grantees will continue to transform the lives of more young people. The biggest outcome of its grantmaking, however, will be if it helps spread the idea to other organizations.

Museums, community centers, parks, theaters, and schools have yet to fully tap the creative potential of young people to change the world. The Hewlett Foundation notes in What is Creative Youth Development? that “the primary challenge for the field now is to make its presence known in related fields, such as education, youth development and juvenile justice.”

After all, spreading good ideas and hope is probably the most important outcome of any grantmaking strategy. A family’s donor-advised fund holds this potential. Learn more about how GMA consultants work with donors here.

—–

Prentice Zinn is a senior consultant and principal at GMA Foundations. Contact pzinn@gmafoundations.com

*The name Rudolph is used in this article to preserve the anonymity of GMA’s client.