Given the complexity and scale of climate change, funders can be tempted to defer to the larger powers of government and business innovation for solutions. This is a rational response yet funders’ grantmaking strengths position them to be part of the solution. Philanthropy’s traditional orientation toward people, rather than their ecosystems, may in fact be instrumental to building climate-resilient communities.

Learning through GMA’s Environmental Justice Fund

In this time of heightened concern for the planet, when federal, state, and city governments are setting ambitious sustainability goals, what is the greatest use of philanthropic dollars? In 2021, GMA established the Environmental Justice Fund – a six-month pooled giving and learning program for grantmakers to explore local, inclusive responses to the challenges posed by climate change. (Scroll to bottom for a list of the Fund’s speakers.)

Through expert learning sessions and research, we discovered that investing in people and neighborhoods can be a powerful contribution to climate-resilient communities and a sustainable future. Responding to climate change this way may require rethinking funding strategy slightly and building on funders’ grantmaking strengths.

Respecting Grantmaking Fundamentals

Our colleagues at The Barr Foundation remind us to keep people in the center of the picture. Using familiar frames of reference as a guide, local funders are well-equipped to adapt and be proactive in addressing climate change. Most local funders already possess:

- Deep familiarity with neighborhoods and nonprofits

- Responsiveness to communities most affected by inequity

- Tactical awareness of “asset classes” among nonprofit organizations, and of different approaches ranging from prevention to mitigation

Additionally, while not grantmaking, the investment portfolio of foundations is especially relevant to the issue of climate change, as certain holdings are complicit to the crisis, while others are on the vanguard of innovation and progress.

Identifying Environmental (In)Justice

Funders naturally tackle difficult issues, threats to the communities they support. Environmental change is already apparent in cities like Boston, where threats of flooding and extreme heat draw increasing attention. The State of Massachusetts has adopted a designation – environmental justice population – to prioritize action in low-income areas with high percentages of minority populations and households lacking English language proficiency.

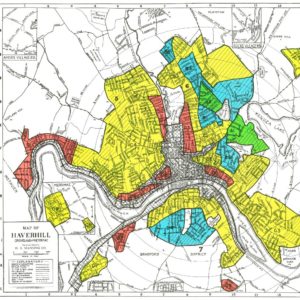

Indeed, there is a social overlay to the problem. Cate Mingoya shared Groundworks USA’s mapping of urban environmental degradation, showing areas of extreme heat and pollution mirroring maps of historic racial redlining.

Guadeloupe Garcia, program officer for the Trust for Public Land in Boston, pointed to the vagueness of the term ‘environmental justice.’ She prefers to accentuate the injustice, present in communities from Chelsea, Massachusetts to Flint, Michigan, and around the world.

Honoring Communities

Despite the physical environment, lower-income neighborhoods have their own agency and vibrancy, as funders have long understood. Local leaders have galvanized action through recently-formed influential nonprofits like the Green Justice Coalition, Neighbor to Neighbor Massachusetts, and Chelsea’s GreenRoots, Inc.

Boston’s longer-established nonprofit environmental infrastructure is also strong. Pioneers such as Alternatives for Community and Environment (ACE) and the Conservation Law Foundation and more traditional conservation entities like The Trust for Public Land and Trustees of Reservations have demonstrated their ability to respond to the leadership of local communities.

Community-led efforts to build climate-resilient communities are pointing the way toward larger effective change, even as cities are leading for the country as a whole.

Linking Policy to Practice

The intersection of public policy and nonprofit activity stands out as a moment of special promise. Massachusetts is likely to receive massive federal funding as part of the US commitment to fight climate change and the state’s recently passed a groundbreaking Climate Bill. The legislation, thanks in part to nonprofit advocacy, includes strong protections for environmental justice communities. Additionally, the City of Boston has its own plan for building climate-resilient communities, as was brought to life by our meeting with Environmental Chief Mariama White-Hammond.

The alignment of public policy and public charities has proven potential to lead to large-scale investment and change. As an example, John Cleveland of the Boston Green Ribbon Commission referred to the Boston Emission Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance (BERDO) which mandates net-zero carbon emissions for Boston’s largest buildings. However, the ordinance leaves untouched the roughly tens of thousands of smaller buildings where most of the city’s residents live – also a significant source of greenhouse emissions. Addressing this omission could be a meaningful challenge for the city’s community development corporations, which have a strong record of improving the quality of life in neighborhoods.

Building a Portfolio

Adopting a venture approach, our group of funders opted to support both smaller and newer organizations where a grant could help to attract other funding and support, and expansion efforts now underway at more established groups. Fund participants chose to recognize a representative group of eight organizations, a number that could easily have been tripled. This portfolio-funding seems best, given the steepness of the challenge and, also, the high level of inter-agency collaboration present and needed in the environmental field.

See a list of the eight recipients of $20,000 unrestricted grants here.

Beyond strength in numbers, there is the element of time, and long-term relationships. Fund speaker Penn Loh pointed to the nonprofit sector’s historic importance in the leadership supply chain; nonprofit leaders often “graduate” to positions of influence in philanthropy and government. This progression is generally made possible by years of sustained support—another key grantmaking fundamental.

The possible responses to the climate crisis are numerous, ranging from policy work to litigation to large-scale initiatives. Investing in climate-resilient communities may bear the greatest results for philanthropy. If people are the leading cause of climate change, they are also its solution and the most gratifying responses can occur at the local level.

As the poet Joseph Brodsky once noted: “And the clearer the song is heard/the smaller the bird.”

———-

Contact Phil Hall, GMA’s Director of Grantmaking, for more information about the Environmental Justice Fund. Visit GMA’s website for a list of participating funders and the organizations selected for unrestricted grants.

The Environmental Justice Fund’s work was guided in large part by a generous group of recognized experts; we provide this list so that you might learn more about their work.

- Mariella Tan Puerto and the Climate Team of The Barr Foundation

- Maria Belen Power, GreenRoots, Inc.

- Staci Rubin, Conservation Law Foundation

- Mariama-White Hammond, City of Boston

- John Cleveland, Boston Green Ribbon Commission

- Cate Mingoya, Groundworks USA

- Penn Loh, Tufts University and chair, Hyams Foundation (former ED, Alternatives for Community & Environment)

- David Queeley, Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation

- Guadalupe Garcia Rodriguez, Trust for Public Land

- Rachel Leon, The Park Foundation (past president, Environmental Grantmakers Association)

- Ann Fowler Wallace, The Funders Network